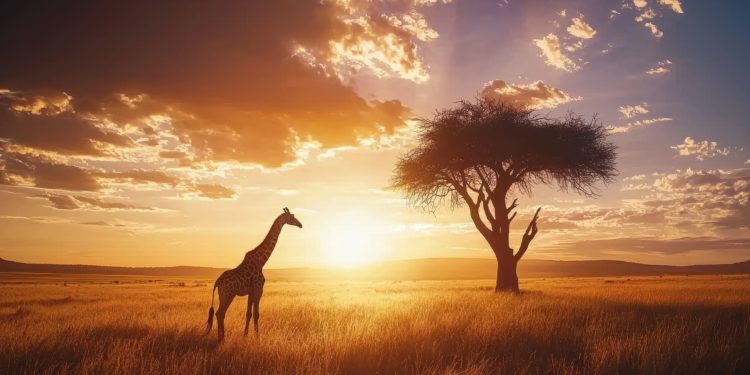

There’s a certain kind of sunset in Kenya that makes people go quiet.

It’s not just the colours — though yes, the sky really does turn into streaks of gold and burnt orange, like someone set the horizon on fire. It’s the way the light falls on the open plains, the way the silhouettes of giraffes stretch long against the sky, the way people instinctively lower their voices — as if not to interrupt something sacred.

We’ve watched first-time travellers fall silent in that glow, their phones forgotten on their laps. It’s usually around then that it sinks in: this isn’t just another holiday. It’s something else entirely.

The first safari has a way of waking up all your senses. It begins with the early morning chill as you ride out in an open vehicle, layered in blankets and quiet anticipation. The sun hasn’t quite risen yet, but the land is already stirring. Then — without warning — you spot your first elephant. Or a lion stretched out in the grass. Maybe it’s a dazzle of zebras or a curious warthog that locks eyes with you. Whatever it is, you won’t be ready for the feeling.

We’ve seen eyes well up. We’ve heard people whisper, “This can’t be real.” And we’ve learned not to interrupt. That moment belongs to them.

It’s not always the big things that leave a mark, though. Sometimes, it’s the silence. The true, bone-deep silence of the wild — not the kind you get with noise-cancelling headphones, but the kind that lives between the hum of cicadas and the chirping of crickets on red earth.

There’s a shift that happens in the bush. Layers fall away. People slow down. At night, around the fire, they open up — telling stories they’ve never told, laughing louder than they have in years, staring up at a sky filled with stars they never knew existed.

It’s beautiful to witness. And a little heartbreaking too — especially on the last day, when the bags are packed, and the vehicles are loaded. The hugs last a little longer. The eyes linger over the horizon, trying to memorise every last inch of it.

Someone always says it, every time: “I don’t think I’m ready to go back.”

And truthfully, no one ever is.

You carry the dust home in your clothes, the smell of campfire in your hair, and something softer in your chest. People will ask you how it was, and you’ll fumble for words — because how do you explain the feeling of coming face to face with something ancient and wild and alive?

You’ll just smile, and maybe say, “You had to be there.”

And you’ll mean it.