The landscape of carbon credits is rapidly taking shape in Kenya, representing a significant shift in how environmental conservation is valued. This system, which turns the protection of natural resources into a tradable commodity, is creating new economic opportunities while raising important questions about equity and governance. A report by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) shows that Africa contributes to less than 5.0% of global Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) and trade; thus, carbon markets gives Kenya and Africa at large an opportunity to contribute in the global trade.

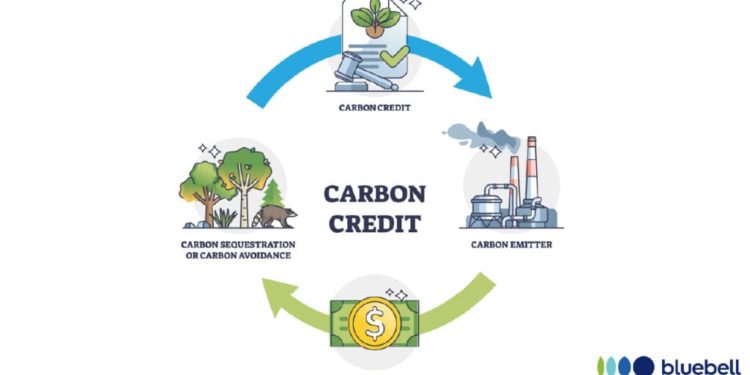

At its core, a carbon credit represents one tonne of carbon dioxide either removed from the atmosphere or prevented from entering it. Kenya’s participation in this market primarily happens through the voluntary carbon market, where corporations and individuals purchase credits to offset their emissions. The country’s natural assets, including forests, rangelands, and coastal mangroves, position it ideally for this emerging economy. These ecosystems serve as effective carbon sinks, and their protection generates credits that can be sold on the global market.

The mechanism shows tangible benefits on the ground. Community-led initiatives like the Mikoko Pamoja project in Gazi Bay demonstrate how mangrove conservation can generate revenue while preserving biodiversity. Similarly, the Northern Kenya Rangelands Carbon Project has implemented sustainable grazing practices that increase carbon storage in soil while supporting pastoralist communities. The revenue from these projects’ funds local development priorities such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure, creating a direct link between conservation and community improvement.

However, this promising field faces significant challenges. The distribution of benefits remains a contentious issue, with concerns about whether local communities receive fair compensation for their role in maintaining these ecosystems a report by BCG highlighted this as the main problem. The complexity of carbon project development often requires international partners, sometimes creating power imbalances in negotiations. Additionally, the Kenyan government’s proposal to claim a significant share of carbon credit revenues has sparked debate about the appropriate balance between national interests and local community benefits.

The future of carbon credits in Kenya will depend on developing transparent frameworks that ensure fair benefit sharing while maintaining the environmental integrity of the projects. As the market evolves, there is potential to expand beyond nature-based solutions to include initiatives like clean cookstove distribution and renewable energy projects. With careful management and inclusive policies, carbon credits could represent more than just environmental protection they could become a sustainable source of economic development that rewards Kenya for its natural stewardship.